신경퇴행질환의 발생과 장의 역할

Development of neurodegenerative disorders and the role of gut

Article information

Trans Abstract

Neurodegenerative diseases are caused by the interaction of genetic susceptibility and environmental factors. Although it has been revealed that α-synuclein and tau protein are the key players in neurodegeneration, the process of where they originate and how they make the disease is still unclear. The gut must coexist with various bacteria and inevitably affect the body. Recent studies have revealed that the nervous system and the gut interact, bringing one step closer to the mystery of how neurodegenerative disorders occur. The most common prodromal symptom of Parkinson disease is constipation. Several studies have confirmed that intestinal alpha-synuclein deposition is prominent in patients with Parkinson disease and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder, and pathological changes can be transmitted through the vagus nerve. In this sense, there has been a hypothesis to divide the process into 2 types, brain-first versus body-first, but it is still controversial. It is unclear whether Alzheimer disease is the starting point for pathological changes in the gut like Parkinson disease. However, common pathomechanisms could be applied to both diseases: disrupting the gut and blood-brain barriers, facilitating inflammations, and engaging hormones. Further studies on the gut-brain axis are required to predict and prevent neurodegenerative diseases.

서론

의료기술의 발달과 함께 기대여명이 빠르게 증가하면서 전 세계적인 고령화가 가속화되고 있다[1,2]. 이로 인해 다양한 신경계 질환들의 유병률이 급격하게 증가하고 있는데, 특히 파킨슨병(Parkinson disease)과 알츠하이머병(Alzheimer disease) 등의 신경퇴행질환의 증가세가 가파르다[3]. 신경퇴행질환의 공통적인 위험인자가 바로 나이이기 때문이다.

고령에서 주로 발생하는 신경퇴행질환들은 유전적인 감수성(genetic susceptibility)과 환경적 요인(environmental factor)의 상호작용으로 발생하기 때문에 일부 유전 질환을 제외하고는 대부분 원인을 하나로 특정하기 어렵다. 알파시누클레인(α-synuclein), 타우단백(tau protein) 등이 신경퇴행질환의 주요 기착지라는 것이 밝혀졌지만, 이들이 어디서부터 생겨나서 어떻게 병을 만들어가는지에 대한 과정에 대해서는 아직 불명확한 부분들이 많다.

장은 몸 속에 있지만 동시에 피부처럼 외부 환경과 접하고 있다. 주로 음식물을 소화시켜 영양분을 흡수하는 역할을 하기 때문에 매우 많은 일을 하는 기관이다. 다양한 세균들과 함께 공존해야 하는 환경이므로 이들과 필연적으로 영향을 주고받을 수밖에 없다. 식습관이 장내세균총의 구성에 영향을 주고, 장내세균총은 장운동, 음식물 및 약물의 흡수 등에 관여한다.

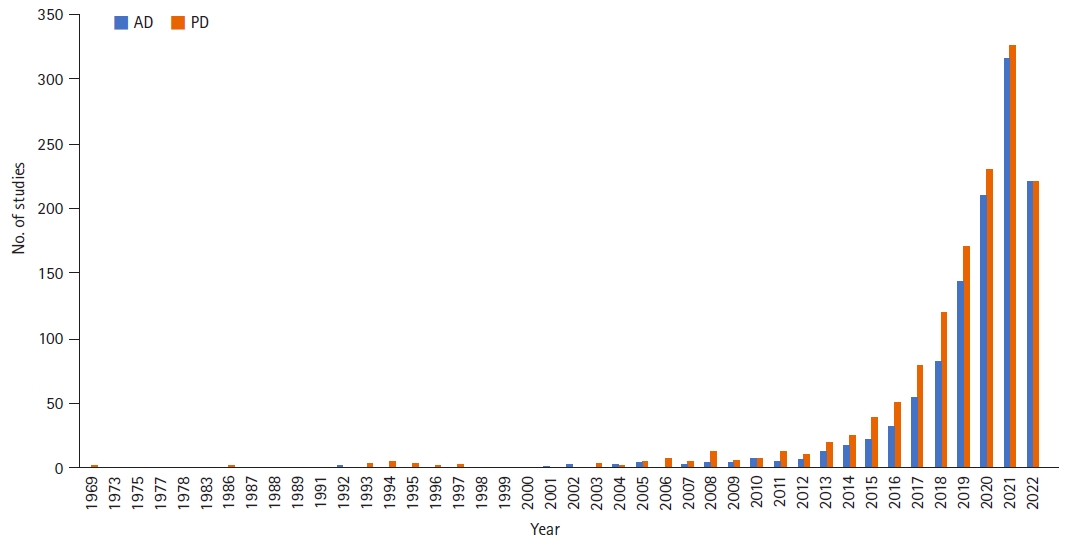

서로 멀리 떨어져 있는 것처럼 보였던 신경계와 장이 최근 여러 연구를 통해 서로 긴밀하게 영향을 주고받는다는 것이 알려지게 되었다. PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/)에서 2022년 8월 6일 현재 ‘gut & Alzheimer’와 ‘gut & Parkinson’으로 검색한 결과 각각 1,041건, 1,232건의 연구가 검색되었고 2010년 이후에 폭발적으로 연구가 증가하였음을 알 수 있다(Figure 1). 특히 신경퇴행질환의 발생에 있어 장과 장내세균총의 역할을 강조하는 연구들이 보고되면서 관심이 더해지고 있는 상황이다. 본 종설에서는 대표적인 신경퇴행질환인 파킨슨병과 알츠하이머병의 발병에 장이 어떤 영향을 주는지에 대한 내용을 정리해 보고자 한다.

장으로부터 신경퇴행질환의 병리변화가 시작하는가?

1. 파킨슨병

1) 전구증상

파킨슨병은 주로 알파시누클레인과 루이소체(Lewy body)가 신경세포에 침착되고, 이로 인해 해당 신경세포들이 사멸하면서 나타나는 질환이다[4]. 일반적으로 환자가 신경과 의사를 찾아오는 시기는 느리고(bradykinesia), 떨리고(tremor at rest), 뻣뻣하고(rigidity), 구부정한 자세(stooped posture)를 취하게 될 때(즉 운동증상이 나타날 때)이지만, 많은 환자들이 운동증상이 나타나기 이전부터 변비(constipation), 후각소실(hyposmia), 우울증(depression), 렘수면장애(rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder) 등의 전구증상을 겪는 것으로 알려져 있다[5,6].

이러한 전구증상 중에 가장 이른 시기에 나타나는 증상이 변비이다. 연구마다 차이는 있으나 대략 운동증상이 나타나기 15년 이상 전부터 나타나는 것으로 보고된다[6]. Braak stage I에서는 미주신경의 등쪽운동신경핵(dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus)이 침범되므로 변비가 유발된다고 볼 수도 있겠지만[7], 그 이하 레벨인 미주신경(vagus nerve)이나 장신경총(enteric plexus)이 침범되어도 변비는 발생할 수 있다.

2) 장으로부터 뇌까지

파킨슨병에서 루이소체가 장내에서도 발견되었다는 연구는 약 40년 전부터 있었다[8,9]. 식도부터 직장까지 거의 전 위장관에 걸쳐 루이소체가 발견되었으나, 한동안 적극적인 후속 연구는 진행되지 않았다. 2006년 Braak 등[10]이 파킨슨병 환자에서 점막하신경총(submucosal plexus)과 근육층신경총(myenteric plexus)에 루이소체가 침착되었음을 다시 한번 보고하였고, 이 루이소체가 미주신경을 통해 중추신경계로 전달되었을 가능성을 제기하였다. 즉 외부 환경과 맞닿아 있는 장으로부터 알파시누클레인과 루이소체의 침착이 시작되고 중추신경계로 이어지는 통로인 미주신경을 통해 전달되었을 것이라는 가설이다.

이 가설이 입증되기 위해서는 몇 가지 증명이 필요하다. 우선, 파킨슨병 환자의 위장관에서 파킨슨병이 없는 그룹에 비해 알파시누클레인과 루이소체 침착이 확연해야 한다. 연구마다 다소 차이는 있으나 Braak 등[10]의 보고 이후 진행된 대부분의 연구에서 파킨슨병에서의 위장관 병리변화가 두드러졌다[11]. 둘째, 알파시누클레인 침착으로 인한 병리변화가 미주신경을 통해 전달될 수 있어야 한다. 쥐와 원숭이를 이용한 동물실험을 통해 위장관에 루이소체 유사체를 주사하였을 때 미주신경을 통해 뇌로 전달됨을 확인한 연구들이 있다[12,13]. 셋째, 미주신경을 절단하면 병리변화가 전달되지 않아야 한다. 쥐를 이용한 실험에서 위장관에 알파시누클레인을 주입한 이후 미주신경을 절단한 경우 외인성 알파시누클레인에 의한 병리변화가 뇌에서 발생하지 않음을 확인하였다[14]. 사람에게서 동일한 실험을 할 수는 없지만, 미주신경절제술(vagotomy)을 받은 사람들을 수년간 추적관찰한 결과 줄기미주신경절제술(truncal vagotomy)을 시행한 그룹에서 파킨슨병의 발생률이 낮음을 확인하여, 간접적으로 파킨슨병 병리변화의 시작이 위장관일 가능성을 제시하였다[15,16].

3) Brain-first versus body-first

파킨슨병의 전구증상 중에 가장 파킨슨병에 특이적인 증상은 렘수면장애이다. 렘수면장애가 있는 경우의 상대위험도가 50 정도로 모든 전구증상 중에 가장 높다[6]. 따라서 렘수면장애가 있지만 아직 파킨슨병의 운동증상이 나타나지 않은 상황에서 신체의 어느 부위를 더 많이 침범했는지를 알면 병의 진행 방향을 가늠할 수 있을 것이다.

2019년 변비, 렘수면장애, 자율신경계증상을 가진 전구단계의 루이소체연관질환 의심환자를 대상으로 도파민운반체영상(dopamine transporter scan)과 metaiodobenzylguanidine 심근스캔(MIBG myocardial cintigraphy)을 시행한 연구가 있다[17]. 해당 연구에서 전체 대상환자 18명 중에 도파민운반체영상에서 양성을 보인 경우는 56% (10명)인 반면에, MIBG심근스캔에서 양성을 보인 경우는 94% (17명)이었다. 해부학적 위치를 고려하면 운동증상을 대변하는 흑색질의 도파민 세포의 사멸이 본격적으로 일어나기 전에 이미 심장의 자율신경이 영향을 받았다는 뜻이므로 병리변화가 몸으로부터 출발하여 뇌로 진행하였다는 가설이 힘을 얻는다(body-first type).

그러나 모든 파킨슨병 환자들이 렘수면장애를 가지고 있는 것은 아니다. 알파시누클레인 병리변화가 주변으로 번져 나가는 특성을 감안할 때, 렘수면장애가 없는 파킨슨병 환자들은 렘수면장애가 있는 경우와 병리의 출발지점이 다르다고 생각할 수 있다. 이러한 가설을 바탕으로 특발성렘수면장애에 렘수면장애가 동반된 파킨슨병과 그렇지 않은 파킨슨병을 추가하여 MIBG심근스캔과 donepezil positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT)를 수행한 연구가 있다[18,19]. MIBG심근스캔은 예상대로 파킨슨병 여부와 관계없이 렘수면장애가 있으면 대부분 이상이 나타났고, 렘수면장애가 없는 파킨슨병에서는 상대적으로 정상인 경우가 많았다. 장운동을 반영하는 donepezil PET/CT도 MIBG심근스캔 결과와 유사한 패턴을 보였다. 결국 렘수면장애가 없는 파킨슨병은 신체의 아래 부분으로부터 병리가 진행되어 온다는 근거가 부족하다(brain-first type).

병리변화의 시작지점을 중심으로 파킨슨병의 타입을 구분하는 방식이 바로 brain-first versus body-first 가설이다. 이를 뒷받침하는 다양한 실험적, 임상적 근거들이 있으나 비판적인 시각도 존재한다[20]. 비록 렘수면장애가 루이소체연관질환에 특이적이라고는 하지만 아밀로이드(amyloid)나 타우단백 관련 질환에서도 보고된 바 있어 허점이 존재한다. 이보다 더 중요한 것은 렘수면장애가 있는 환자의 뇌에 이미 알파시누클레인 침착과 연관된 병리변화와 세포사멸이 발견되었다는 점이다. 결국 이질성(heterogeneity)을 가진 파킨슨병이라는 큰 질환군을 단순한 방식으로 나누는 것 차체가 어렵다는 것이다.

2. 알츠하이머병

파킨슨병과 달리 알츠하이머병의 병리변화가 장으로부터 시작하는지 여부는 불분명하다[21]. 일부 장내에서 타우단백이 발견되었다는 보고가 있기는 하지만[22,23], 다른 연구에서는 알츠하이머치매와 비알츠하이머치매 군 모두에서 발견되지 않아서 일관된 결과는 아니다[24]. 최근 시행한 연구에서는 장내 타우단백이 타우관련 신경퇴행질환과 대조군 모두에서 발견되었으나, 양 군 사이의 차이는 없었기 때문에 질환특이성은 적은 것으로 생각된다[25]. 더구나 파킨슨병에서와는 달리 줄기미주신경절제술을 시행한 그룹에서 알츠하이머병의 발생 확률이 더 높지 않았기 때문에 사람 대상의 임상연구에서도 근거도 부족하다[26]. 파킨슨병에서는 변비가 운동증상을 선행하는 반면 알츠하이머병에서는 이러한 관계가 명확치 않은 점도 이를 뒷받침한다.

신경퇴행질환의 발생에 영향을 주는 기타 장의 역할

파킨슨병에서 장의 병리변화가 미주신경을 통해 뇌로 전달되는 것이 주요 원인일 수 있다는 가설이 매우 매력적이어서 눈길이 가지만 장의 역할이 단지 병리변화의 출발점에만 멈춰 있는 것은 아니다. 알츠하이머병을 비롯한 다른 신경퇴행질환에서도 장 혹은 장내 마이크로바이옴(gut microbiome)의 변화가 병의 발생과 진행에 영향을 준다는 연구결과들을 볼 때, 미주신경을 통한 기전 외에도 신경퇴행질환에 영향을 주는 다양한 간접 경로가 존재할 것이라는 점을 짐작할 수 있다[27].

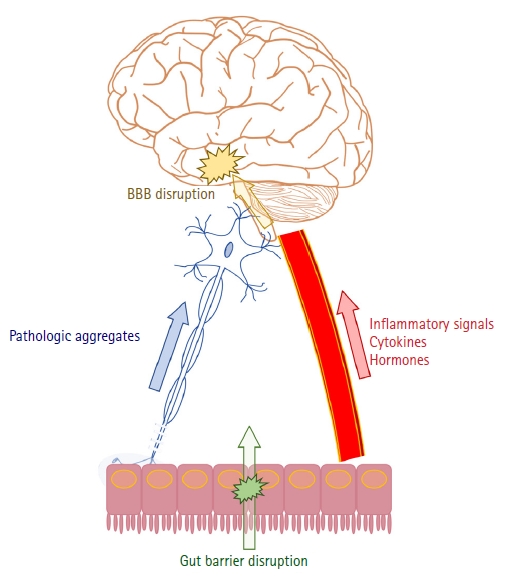

그 중 가장 중요한 부분을 차지하는 것은 염증이다. 전신 혹은 신경계 염증이 파킨슨병과 알츠하이어병을 비롯한 다양한 신경퇴행질환의 발생에 영향을 준다는 것이 잘 알려져 있다[28]. 장이 이러한 염증 변화에 있어 중요한 역할을 담당한다는 것이다. 장내 마이크로바이옴은 각종 매개물질을 통하여 숙주의 면역기능에 영향을 준다[29]. 예를 들어 장내 세균에서 분비되는 지다당(lipopolysaccharide)은 혈류를 거쳐 뇌에 신경염증을 유발할 수 있다[30]. 세균의 지다당으로 인해 혈액뇌장벽(blood-brain barrier)의 투과도가 증가하여 염증세포의 진입이 용이해지기 때문이다[31]. 장내 세균으로부터 기인한 단쇄지방산(short-chain fatty acid)도 뇌에서의 면역기능을 담당하는 미세교세포(microglia)의 성숙에 관여함으로써 염증 조절에 영향을 준다. 이처럼 장과 관련된 신경계 염증이 알츠하이머병 발생에 뚜렷한 영향을 준다는 것은 여러 연구를 통해 밝혀졌으며[32], 항생제 치료나 건강한 장의 마이크로바이옴 이식이 염증의 감소와 병리변화를 줄여주었다는 동물실험 결과를 통해 향후 마이크로바이옴의 조절을 위한 예방 또는 치료의 가능성을 엿볼 수 있다[33]. 알츠하이머병처럼 파킨슨병에서도 장내 마이크로바이옴과 연관된 염증반응과 혈액뇌장벽 투과도 증가가 신경퇴행변화에 영향을 준다는 보고가 있다[34,35]. T세포 및 TLR4 매개 염증반응이 주요 기전으로 제시되어 있으나 추가 연구가 필요하다[36,37]. 외부와 내부를 분리하는 장과 뇌의 장벽의 손상(disruption of gut and blood-brain barriers)은 염증이 잘 전달되기 위한 중요한 기전 중에 하나이다[38,39].

그 밖에 장내 마이크로바이옴이 호르몬에 영향을 주어 알츠하이머병에 관여한다는 연구도 있다[40]. 그렐린(ghrelin)은 포도당 및 지질대사 뿐만 아니라 학습 및 기억 등의 고위뇌기능 및 미토콘드리아 호흡에도 관여한다. 렙틴(leptin)은 시상하부에 작동하여 포만감을 느끼게 함으로써 식욕을 억제하는 기능을 담당한다. 이러한 기본 기능 외에도 그렐린과 렙틴이 Aβ올리고머에 의해 유도된 독성으로부터 세포를 보호하는 인자로 작용한다는 보고가 있어 알츠하이머병의 발병과 연관성이 있는 것으로 생각된다[41]. Glucagon-like peptide 1과 glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide 유사체 등 글루카곤과 연관된 물질들도 신경보호효과가 있어 발병에 일정부분 역할을 할 것으로 추정된다[42,43]. 파킨슨병에서도 유사한 기전으로 발병기전에 관여할 것으로 추정되며, 이를 활용한 임상시험도 진행되고 있다[44,45].

결론

Figure 2는 현재까지 장으로부터 비롯되어 신경퇴행질환의 발생에 영향을 주는 것으로 알려진 요인들을 도표로 정리한 것이다. 파킨슨병과 알츠하이머병은 대부분의 기전을 공유하지만, 장으로부터 병리변화가 시작되어 미주신경을 통해 뇌까지 전달되는 기전은 현재까지의 연구들을 바탕으로 볼 때 파킨슨병만의 특징으로 생각된다. Figure 1을 보면, ‘Alzheimer’를 검색어로 입력한 경우의 첫 연구발표는 1975년인 반면, ‘Parkinson’으로 검색하였을 때는 1969년이었다. 즉, 파킨슨병과 장과의 연관성에 대한 연구가 상대적으로 더 빨리 시작되고, 더 많이 이뤄지고 있다고 볼 수 있다. 이는 앞서 살펴본 바와 같이 파킨슨병에서 장과 관련된 비운동증상이 많고 미주신경을 통한 병리변화가 잘 증명되었기 때문이 아닌가 추정된다.

신경퇴행질환은 오랜 기간에 걸쳐서 서서히 진행하므로 하나의 원인을 특정하기 어려운 경우가 대부분이다. 유전적인 감수성과 환경적 요인의 상호작용으로 인해 병이 발생하며, 이 중에서 교정이 가능한 것은 환경적 요인이다. 이러한 점에서 장내 환경이 신경퇴행질환 발생의 중요한 축을 담당한다는 최근의 연구결과들은 미지의 세계에 한걸음 다가서게 함과 동시에 신경퇴행질환 극복의 희망을 갖게 하였다. 후속 연구들을 통해 신경퇴행질환을 미리 예측하고 예방할 수 있는 다양한 방법이 개발되기를 기대한다.

Notes

Conflict of Interest

The author has no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

None.